Construction

|

This is an interview that Richard Jones gave in 2006 for The Viol, (Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society (UK), for a series on instrument makers. This page includes some additional images)

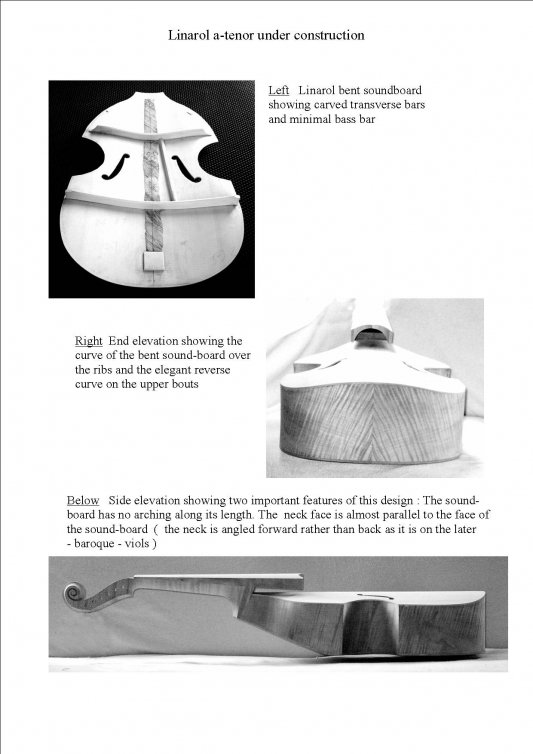

Richard Jones makes renaissance viols to commission in his seaside workshop on the north Solway shore in southwest Scotland. Based on the single extant instrument made by Francesco Linarol (c1540) which is now in the care of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, he sizes them up or down to produces sets of viols that play at modern pitches and which accord to the dispositions of viols used in the first half of the 16th century as described by Ganassi and others:- Top voice in a, middle voices in d and bass in A. He made his first copy of the g-tenor size viol in 1986 and has since added a conjectural d-treble to his range. He uses Scottish hardwoods where possible and has a tree-planting policy to replace more wood than he uses. From making instruments for his own group to play, he now has a growing waiting list.

What is your making background ?

I was brought up in a culture of workshops and making – My father built us a workshop in the garden and equipped it so when something was wanted or you got excited about something, you made it or did it. I was at a school, Bedales Junior, where the arts and crafts were encouraged. The whole Bedales experience, aged four to twelve, included proper woodwork lessons, good long lessons that provided a really good grounding as a well as a love of woodwork. Then I used to go down to the local joiner’s shop. He let me come in there an hour before breakfast each morning working opposite him on the bench making whatever I wanted with his off-cuts. I made stools, and tables and carved number signs for people’s houses. The first instrument I made was an electric guitar. When I was fourteen I fell in love with the sound it made and it was certainly never going to be allowed on my birthday or Christmas list, so I set about making one. I used to cycle over to Cambridge and looked in Miller’s music shop window where there was a Hofner Futurama or Colorama. Eventually I did some drawings and borrowed a Spanish guitar to see how big it was. I don’t remember the design process at all but one way and another I put together something that was an electric guitar. I got the help of the physics teacher at school though the instrument was built in the garage at home. It was pretty home made but I still have that instrument. I made my first bass guitar at nineteen because that was what I was playing in a band. I made three or four of those, the first one at the end of my time at Friends’ School, Saffron Walden just before going to Loughborough College to train to teach woodwork. Two years after that I went to Scotland as a woodwork teacher which I did for thirty years.

How did you come upon early music ? Who inspired you ?

In the 1970s I went to Dumfries to see one of Ashley Hutchings’ groups – I think it was the Albion Band – and there was this wonderful mixture of folk music and rock music. I was listening to Radio 3 one morning and one of the tunes they played I recognised from the Ashley Hutchings concert. The announcer said it was a dance from Susato,’La Morisque’, played by The Early Music Consort of London directed by David Munrow. There was this sound of shawms and sackbuts, I thought it was stunning, there was a texture there that was far more exciting, more colourful than any of the smooth classical sound of trombones and oboes. I caught the early music bug and was so lucky. Within weeks of hearing that record I met a man in Edinburgh who was making a set of regals for Christopher Hogwood who played on that record, so very quickly I was drawn into this exciting world which in the 1970s had a vibrancy that has matured now. I wanted to have recorders, crumhorns and shawms, mostly wind instruments.

tying frets

What made you move onto the viol then ?

In 1978 I was sitting at home playing my father’s cello one holiday and the thought occurred to me that with my bass guitar left hand technique and a bit of practice with the bow, I could master this and learn to play the viol. I thought of the family motto ‘ If you want it make it’ but I didn’t have the confidence to make a viol from scratch and I didn’t know anyone who made viols. An easy option was to buy a Hopf Viol Kit from The Early Music Shop. I had also come across Eph Segerman at that stage and between phone calls and correspondence with him I looked at how I might adapt the instrument to make it closer to the 16th century viol than an all-purpose viol. The ‘all-purpose viol’ is a phrase I don’t use by accident. Michael Morrow wrote in Early Music around this time that he thought that viol players were all too cheerfully complacent. They wanted an all-purpose style and instrument and it was only when we recognised the differences between different periods and types of viol that we would really understand this music.

So how did you come to focus on the Linarol ?

I had already taken my Hopf viol to Northern Renaissance Instruments in Manchester for stringing to Eph and Djilda Segerman, a meeting I found so inspiring. There was lots of discussion about strings, construction and the precise changes of the viol through its history. The whole idea of the right kind of instrument and approach was so much their focus. Djilda gave me a full-size drawing of the Linarol viol. By the early eighties Martin Edmunds and Ian Harwood had written pretty thoroughly on the extant renaissance viols – looking at this other family of viols it was obvious that if I was going to play this music ( early to mid-16th century ) I should be exploring what was a more appropriate viol than an all-purpose, metal strung, sound-posted creature. I read Martin Edmunds and could see that was were more parallels in the construction of the Linarol viol with its bent front with guitars, which I had made, than there was with the Ciciliano type with their carved fronts which I had little experience of and didn’t understand the working of. So it was the similarity with the guitar but also the fact that you could make the soundboard from a flat guitar piece which was cheap rather than a split violin soundboard which was more expensive, that decided me on the Linarol.

soundboard underside

What were the difficulties you encountered ?

That would take a book to answer ! The same difficulties as every other maker has – ribs that broke in the bending, getting neck angles exact, choosing strings, making pegs work properly, getting the action right but the unusual thing about the Linarol is that the soundboard is not carved from a solid block of wood ( there is no carving in the belly at all as in the later English bent-front viols). The soundboard is jointed and planed flat to about 2.7 mm for a tenor, cut roughly to shape and then bent along its length and grain with the edges folded down. If you do it carelessly the grain will split and sure enough, I broke my first one. I had cleared the workshop because I was so frightened ; getting this bending iron which was a piece of pipe heated by a gas torch to the right temperature. That was the biggest difficulty which I have refined over the years – a major realisation was that the shape of the soundboard is not a cylindrical bend but a conical one which means at no time is the iron going right down the grain.

carving a neck

Have you had to change anything from the original ?

I have tried to make as few changes from the original which is, I believe, as it was when it left Linarol’s workshop. As soon as you start saying – I can improve this – you run the risk ( as has happened throughout the history of the early music revival ) of losing what you were trying to do. I did find that the originals peg-box is very tight and the pegs are very close together so the strings tend to foul the edge of the peg-box, so I have made tiny alterations without compromising the aesthetics. It makes the instrument more practical and makes no compromise to the way it works acoustically – that’s crucial.

What woods have you decided to us and why?

I have a lovely source of interesting Scottish grown sycamore – the man who supplies me with wood had a very responsible approach to cutting and re-planting and has a good feeling for the kind of wood I want, the more interesting grains, curly, quilted or rippled sycamore for the backs and ribs which is similar to the original, but which might be maple. My first copy was made from alder because that’s what I had and I’ve used yew which is attractive but difficult to find clean pieces. I would like to try other woods – I’m about to make one from lace-wood ( London Plane) – but prefer to use home-grown woods. If you know where a tree grew and was felled and that there is a re-planting scheme in operation, that feels better than going to some timber merchant and buying wood whose origin you don’t know. With soundboards you have to trust the merchant – spruce does grow in Scotland but far too fast to be useful to instrument makers.

varnishing an A-Bass viol

You have avoided developing a process that would allow elements of mass production to speed the making. Is this a matter of philosophy?

That question sounds as if it comes from someone at the bottom end of my waiting list. Yes, it is a philosophical decision. I don’t know that it necessarily has a huge effect on the instrument but I know it has on me. It suits me to start out with a bundle of wood and the name of a person in my head, to make that person an instrument and be totally engaged with that piece of wood and not get halfway through and start to wonder if I’ve done six necks, when I need seven. That would be a sensible way to work but it is this engagement with each instrument that keeps it alive for me. I’m not interested in setting up a factory to mass-produce instruments and make a fortune – as soon as you focus on the commercial and the efficient you run the risk of losing that engagement. I don’t ever want to get bored with what I do.

How long does it take to complete an instrument in this bespoke manner – say a d-bass?

It would be nice to put a precise number of hours on it but I never have. The joinery (building the instrument ) usually takes about four or five weeks, but the varnishing can take two or three months. I don’t have a drying cupboard so I’m reliant on the sunshine.

How did you first come to make an instrument to sell?

By the 1990s I had five Linarol viols of my own which we often played for pleasure with friends so people were getting to know the sound of a set of these instruments. In 2000 the school where I had worked for thirty years closed. I spent six months on the dole deciding what I was going to do for the rest of my life, knowing that there were people who had asked me if I would make them instruments but to whom I had always said no, not having had the time before. So I started making professionally with a waiting list. The first set of viols I made was for Patsy Campbell of The Edinburgh Renaissance Band (an instance of authentic and invaluable patronage ) We had run two well-supported renaissance viols courses in Scotland and been having viol lessons with Alison Crum for several years. That had provided a valuable exchange over the years – to an instrument maker the perspective of a professional viol player is hugely important – she had always been a great supporter of renaissance viols, one of the few professional standard bearers. She did offer a cautionary comment about the likely demand for such instruments.

forged eyes to fix hook hook to hold the tailpiece

Would you say you employ a marketing strategy to sell such specialised instruments?

I’m not quite certain where evangelising, which I’m happy to admit to, ends and marketing, which can be awkward around players you know, begins. My feeling was that if people who played viols knew about this very special sound colour, playing anything from Dowland backwards, they would love it too. We have looked for opportunities for people to hear how these instruments work together and one of the most exciting events has been The Greenwich International Early Music Festivals where we have taken our own viols and viols I have made for other people and offered visitors the opportunity to play the viols as a set, anything from three to six players. I have a website and I print brochures which is as close to a marketing strategy as I get. It’s mostly word of mouth. We have provided instruments for Renaissance Viols Playing Days for The Early Music Forum of Scotland for several years and visited courses at Durham, Ambleside and Netherurd as workshop contributors, introducing their volunteer viol players to the earlier instruments and their repertoire.

The conjectural d-treble; how did this come about?

Thomas Munck wrote a piece in the VdGS newsletter, a friendly broadside asking why it was that whenever people who play renaissance viols see a piece of music that goes out of the comfortable range of an a-tenor, they transpose it down a 4th. He went on, consistently and convincingly, to make the case for there being a smaller viol size. Thomas sent me a copy of a painting (Three Graces - Hans Baldung Grien c1485-1545) of something he thought might be a treble viol. I thought I could scale the Linarol viol down to a treble size – string length 35-36 cm –so I designed an instrument to play in d at A440. Acoustically and aesthetically it worked beautifully.

Having made one and sold two others, what is your current feeling about the treble?

Musica Antiqua of London played some William Byrd on a recent live concert on Radio 3 using the treble viol I made for Thomas, using a family of Ciciliano viols below. I was very pleased by the way it worked in consort and as a top line instrument. Historically, the jury is still out but then in this field there are a huge number of uncertainties, one has to go forward with a bit of inspiration, best guess and a touch of this-might-have-been. One has to be very careful about being dogmatic. I like to think I’m making an instrument that Francesco Linarol would look at and say ‘That’s interesting’ or ‘I don’t do it that way’ or ‘Yes, that’s worthy of something from my workshop.’

Philip Thorby playing the treble

Any thoughts on the authenticity of surviving viols debate?

We must always be careful. Some of the instruments we thought were authentic turned out to be not but we must also be careful about dismissing the whole lot and saying there is no surviving information. I don’t believe that. There have been alterations to some instruments (as far as I know, not the Linarol) There are three surviving instruments built this way – the Jerg Gerle ( body only but you can see how it was built ) and the Hainrich Ebert ( has been altered but there is information you can gather from it before the alterations) in Brussels. And the Linarol in Vienna.

How do you see the future development of the renaissance viol?

It seems to me that viol players are increasingly looking to have an appropriate instrument so if they want to play Bach and Marais they’ll go to makers who make 7-string viols, use an appropriate bow and technique and that’s a viol. At the other temporal end there are people who are going back to before surviving originals (eg. Roger Rose’s Costa viols for Musica Antiqua of London ) and that’s a viol too. I can’t see us going to narrow back down and expect to have one instrument to do all these things. In the 1970s when I started in early music there were far more people interested in playing and listening to it – it was a kind of fashion item –but it did tend to be a bit all-purpose and inevitably players and listeners will have dropped off, leaving a core of committed musicians to carry on. Over the last year or two I have become aware of players thinking of these instruments not being just the province of Lassus, Ortiz and Willaert but also Byrd, Holborne and Ferrabosco I. By about 2008 there will be six of my large A basses out of the loose so I look forward to the good growling sound of ‘A Sei Bassi’, transposed down, playing somewhere. We might even invite Thomas Munck to play !

Interview devised and conducted by Vivien Jones. August 2006. Powfoot.

working on a neck

|